neural networks in cobol and other creative ways to k*ll yourself

Disclaimer: this is a tribute to the Cruelty Squad video game. Just to showcase how COBOL can still be used in bizarre ways to maximize shareholder value. ✨

Yesterday I opened my inbox expecting the usual sprint cosplay and jira fan fiction. Instead, I got a message from a guy that predates agile, devops, and most human rights:

Naturally, I asked if I could at least sketch the thing in python first. I got this reply:

Alright. Let’s do this.

housekeeping

Before we dive in, I want to vehemently recommend the A Programmer’s Introduction to Mathematics book. It’s a great resource for anyone who wants to understand the math and speak symbols like the grown ups if you have a coding background like myself.

I also suggest taking a look at the 3Blue1Brown series on neural networks. They are very visual and build from the ground up.

We can download the Palmer penguin dataset from Kaggle.

neural what?

A neural network is just a function with knobs.

You give it numbers. It outputs numbers.

The only thing you control is the parameters . Training means adjusting those parameters so future outputs are less wrong than past ones.

There is no intelligence here. No understanding. The network does not know what it is doing. It only knows how to reduce a number called loss.

We’ll use the simplest non-trivial setup: a feedforward network with one hidden layer.

data as numbers, not vibes

The model never sees penguins. It sees vectors.

A vector is just a list of numbers arranged in a specific order. Think of it as coordinates in space, except instead of (x, y, z) you might have (bill_length, bill_depth, flipper_length, body_mass).

Your input is a fixed-length vector of measurements:

This is 4-dimensional space. Each component is a real number.

Your target label is the species encoded as an integer (0 for Adelie, 1 for Chinstrap, 2 for Gentoo):

Yes. That is the point.

Before training, we normalize:

This subtracts the mean and divides by the standard deviation for each feature.

Why this matters: gradient descent assumes each dimension contributes on a similar scale. If one feature ranges in thousands and another in decimals, the optimizer zigzags and wastes steps.

the architecture

A neural network layer is two operations:

- linear combination

- nonlinear distortion

If you stack only linear layers, the whole network collapses into one linear transformation. Depth adds nothing. This is why nonlinearity is mandatory.

Hidden layer:

ReLU is the simplest useful nonlinearity:

It zeroes negative values and leaves positive ones unchanged. Without this, the network is just linear regression wearing a trench coat.

Different kind of exposure.

Output layer:

These are raw scores called logits. They can be any real number.

Final step:

Softmax converts arbitrary scores into a probability distribution that sums to 1:

Shapes:

- maps 4 inputs to k hidden units

- offsets each hidden unit

- maps hidden units to 3 classes

- offsets class scores

turning wrong into a number

The model outputs probabilities. We need a single scalar that measures how bad the prediction is.

For classification, use cross entropy:

Here must be converted from an integer index to a one-hot vector. This is a 3-dimensional vector where the true class gets a 1 and all others get 0. If the true class is 2 (Gentoo):

Why three dimensions? Because we have three species. The vector aligns with the three output probabilities .

The loss reduces to:

If the model assigns low probability to the correct class, the loss is large. If it is confidently wrong, the loss spikes. This is intentional. Wrong certainty should hurt more than uncertainty.

Loss is the only feedback signal the network ever gets.

learning equals nudging numbers

Training means changing parameters to reduce loss.

The rule is gradient descent:

The gradient points toward steeper loss. You step in the opposite direction.

is the learning rate. It controls step size.

Too small: training crawls. Too large: loss oscillates or explodes.

There is no universal value. You pick it empirically.

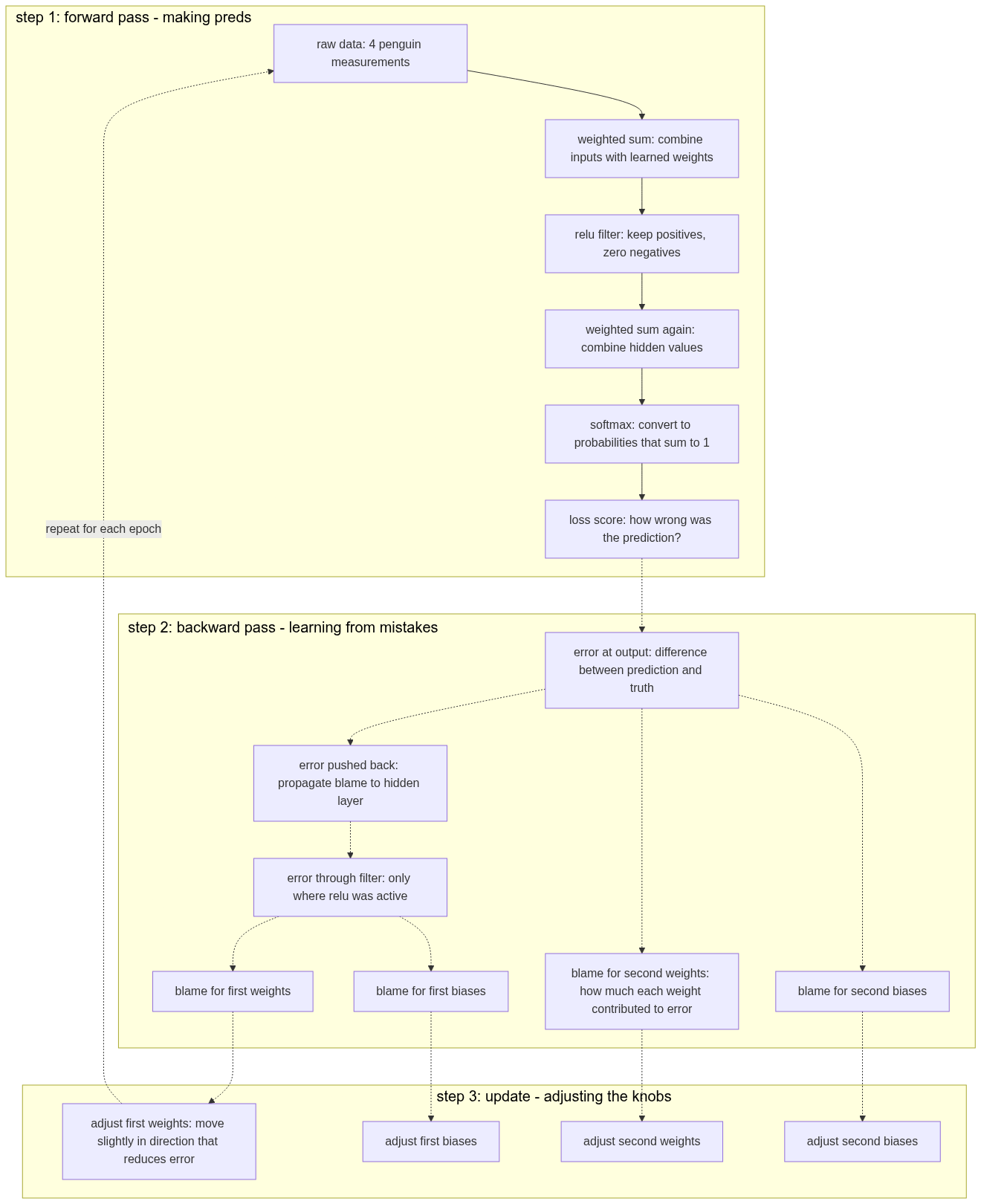

backpropagation, no mysticism

Backpropagation is the chain rule applied to the network graph.

The loss depends on the output. The output depends on the last layer. That depends on the hidden layer. That depends on the input layer.

Backprop computes gradients in reverse order. The notation looks scary but it is just derivatives:

Read as “how much does loss change when I nudge “. That curly symbol just means partial derivative, which is calculus for “change in this one thing while holding everything else constant”.

Nothing flows backward except these derivatives. They tell you which direction to adjust each parameter.

Essentially yes.

For softmax combined with cross entropy, the gradient simplifies beautifully:

full training loop

Training is boring and repetitive:

- take a batch of inputs

- compute predictions

- compute loss

- compute gradients

- update parameters

- repeat

If loss goes down, you are doing something right. If it does not, assume your setup is broken.

They should. It is accurate.

Let’s see the flow in context:

from english to python

Every operation becomes explicit code.

Linear transformation:

def linear(x, W, b):

return x @ W + b

The @ symbol is matrix multiplication. It computes weighted sums of inputs. When you write x @ W, each row of x gets multiplied by each column of W and summed up. It is the same as writing nested loops, but readable.

ReLU and its derivative:

def relu(z):

return np.maximum(0, z)

def relu_grad(z):

return (z > 0).astype(float)

Softmax with numerical stability:

def softmax(z):

exp = np.exp(z - np.max(z, axis=1, keepdims=True))

return exp / np.sum(exp, axis=1, keepdims=True)

One-hot encoding for the target:

def one_hot(y, num_classes):

out = np.zeros((len(y), num_classes))

out[np.arange(len(y)), y] = 1

return out

Cross entropy loss:

def cross_entropy(probs, y):

return -np.mean(np.log(probs[np.arange(len(y)), y]))

Correct. The rest is just calling these repeatedly.

full working code

import numpy as np

import seaborn as sns

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler

# data

df = sns.load_dataset("penguins").dropna()

X = df[["bill_length_mm", "bill_depth_mm", "flipper_length_mm", "body_mass_g"]].values

y = df["species"].astype("category").cat.codes.values

scaler = StandardScaler()

X = scaler.fit_transform(X)

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(

X, y, test_size=0.2, random_state=42

)

# helpers

def relu(z):

return np.maximum(0, z)

def relu_grad(z):

return (z > 0).astype(float)

def softmax(z):

exp = np.exp(z - np.max(z, axis=1, keepdims=True))

return exp / np.sum(exp, axis=1, keepdims=True)

def one_hot(y, k):

out = np.zeros((len(y), k))

out[np.arange(len(y)), y] = 1

return out

def cross_entropy(probs, y):

return -np.mean(np.log(probs[np.arange(len(y)), y]))

# init

np.random.seed(0)

D = X.shape[1]

H = 16

C = len(np.unique(y))

W1 = np.random.randn(D, H) * 0.01

b1 = np.zeros(H)

W2 = np.random.randn(H, C) * 0.01

b2 = np.zeros(C)

lr = 0.1

# training

for epoch in range(150):

# forward

z1 = X_train @ W1 + b1

h = relu(z1)

z2 = h @ W2 + b2

probs = softmax(z2)

loss = cross_entropy(probs, y_train)

# backward

y_oh = one_hot(y_train, C)

dz2 = probs - y_oh

dW2 = h.T @ dz2 / len(X_train)

db2 = dz2.mean(axis=0)

dh = dz2 @ W2.T

dz1 = dh * relu_grad(z1)

dW1 = X_train.T @ dz1 / len(X_train)

db1 = dz1.mean(axis=0)

W1 -= lr * dW1

b1 -= lr * db1

W2 -= lr * dW2

b2 -= lr * db2

if epoch % 50 == 0:

print(f"epoch {epoch}, loss {loss:.4f}")

# evaluation

z1 = X_test @ W1 + b1

h = relu(z1)

z2 = h @ W2 + b2

preds = np.argmax(softmax(z2), axis=1)

accuracy = (preds == y_test).mean()

print("test accuracy:", accuracy)

This outputs:

$ python pengu_nn.py

epoch 0, loss 1.0987

epoch 50, loss 0.9576

epoch 100, loss 0.4045

test accuracy: 0.9701492537313433

Naturally, the Handler hates this.

Great.

the cobol nightmare

You want neural networks in COBOL? Enjoy the pain.

Well, I guess I have to dust off my ancient COBOL books1:

COBOL was built for accountants, not gradient descent. You get fixed-width fields, no arrays the way you want them, no dynamic memory, and arithmetic that feels like chiseling numbers into wet clay.

I will show only the parts that correspond to neural network operations. For the full implementation including data loading, CSV parsing, train-test split, and all the WORKING-STORAGE boilerplate, see the complete source code.

data loading and preprocessing

COBOL loads CSV files line by line, validates against missing values, and encodes species as integers:

* ENCODE TARGET SPECIES AS INTEGER LABELS (0-2).

EVALUATE WS-SPECIES-STR

WHEN "Adelie" MOVE 0 TO D-Y(WS-VALID-ROWS)

WHEN "Chinstrap" MOVE 1 TO D-Y(WS-VALID-ROWS)

WHEN "Gentoo" MOVE 2 TO D-Y(WS-VALID-ROWS)

END-EVALUATE

Normalization is done with the same z-score formula, but spelled out explicitly:

* STEP 5: APPLY Z-SCORE TRANSFORMATION TO ALL SAMPLES.

PERFORM VARYING IDX-ROW FROM 1 BY 1

UNTIL IDX-ROW > WS-VALID-ROWS

COMPUTE D-X1(IDX-ROW) = (D-X1(IDX-ROW) -

WS-MEAN-X1) / WS-STD-X1

COMPUTE D-X2(IDX-ROW) = (D-X2(IDX-ROW) -

WS-MEAN-X2) / WS-STD-X2

COMPUTE D-X3(IDX-ROW) = (D-X3(IDX-ROW) -

WS-MEAN-X3) / WS-STD-X3

COMPUTE D-X4(IDX-ROW) = (D-X4(IDX-ROW) -

WS-MEAN-X4) / WS-STD-X4

END-PERFORM

weight initialization

Python uses np.random.randn(). COBOL implements Gaussian sampling with the Box-Muller transform:

* GAUSSIAN WEIGHT INITIALIZATION USING BOX-MULLER TRANSFORM.

* G(X, Y) = SQRT(-2LN(U1)) * COS(2PI * U2).

PERFORM VARYING IDX-I FROM 1 BY 1 UNTIL IDX-I > 4

PERFORM VARYING IDX-J FROM 1 BY 1 UNTIL IDX-J > 16

COMPUTE WS-RAND-U1 = FUNCTION RANDOM

COMPUTE WS-RAND-U2 = FUNCTION RANDOM

COMPUTE WS-GAUSSIAN =

FUNCTION SQRT(-2 * FUNCTION LOG(WS-RAND-U1)) *

FUNCTION COS(2 * WS-PI * WS-RAND-U2)

* SCALE WEIGHTS DOWN (0.01) TO PREVENT GRADIENT EXPLOSION.

COMPUTE W1-VAL(IDX-I, IDX-J) = WS-GAUSSIAN * 0.01

END-PERFORM

END-PERFORM

forward pass: hidden layer

Python: z1 = X @ W1 + b1

COBOL: explicit nested loops for matrix multiplication.

* HIDDEN LAYER COMPUTATION: Z1 = X * W1 + B1.

PERFORM VARYING IDX-J FROM 1 BY 1 UNTIL IDX-J > 16

MOVE B1-VAL(IDX-J) TO Z1-VAL(IDX-I, IDX-J)

COMPUTE Z1-VAL(IDX-I, IDX-J) =

Z1-VAL(IDX-I, IDX-J) +

(D-X1(IDX-I) * W1-VAL(1, IDX-J))

COMPUTE Z1-VAL(IDX-I, IDX-J) =

Z1-VAL(IDX-I, IDX-J) +

(D-X2(IDX-I) * W1-VAL(2, IDX-J))

COMPUTE Z1-VAL(IDX-I, IDX-J) =

Z1-VAL(IDX-I, IDX-J) +

(D-X3(IDX-I) * W1-VAL(3, IDX-J))

COMPUTE Z1-VAL(IDX-I, IDX-J) =

Z1-VAL(IDX-I, IDX-J) +

(D-X4(IDX-I) * W1-VAL(4, IDX-J))

This is matrix multiplication, expressed as stubbornness.

forward pass: ReLU

Python: h = np.maximum(0, z1)

COBOL: an IF statement in a loop.

* NON-LINEAR ACTIVATION: RELU(Z) = MAX(0, Z).

IF Z1-VAL(IDX-I, IDX-J) > 0

MOVE Z1-VAL(IDX-I, IDX-J) TO H-VAL(IDX-I, IDX-J)

ELSE

MOVE 0 TO H-VAL(IDX-I, IDX-J)

END-IF

forward pass: output layer

Python: z2 = h @ W2 + b2

COBOL: same pattern, different dimensions.

* OUTPUT LAYER COMPUTATION: Z2 = H * W2 + B2.

PERFORM VARYING IDX-J FROM 1 BY 1 UNTIL IDX-J > 3

MOVE B2-VAL(IDX-J) TO Z2-VAL(IDX-I, IDX-J)

PERFORM VARYING IDX-K FROM 1 BY 1 UNTIL IDX-K > 16

COMPUTE Z2-VAL(IDX-I, IDX-J) =

Z2-VAL(IDX-I, IDX-J) +

(H-VAL(IDX-I, IDX-K) *

W2-VAL(IDX-K, IDX-J))

END-PERFORM

END-PERFORM

forward pass: softmax

Python: vectorized exponentials and division.

COBOL: two-pass algorithm with explicit accumulation.

* PROBABILITY ESTIMATION: SOFTMAX(Z2).

* P_i = EXP(Z_i) / SUM(EXP(Z_j)).

COMPUTE P-VAL(IDX-I, 1) = FUNCTION EXP(Z2-VAL(IDX-I, 1))

COMPUTE P-VAL(IDX-I, 2) = FUNCTION EXP(Z2-VAL(IDX-I, 2))

COMPUTE P-VAL(IDX-I, 3) = FUNCTION EXP(Z2-VAL(IDX-I, 3))

MOVE 0 TO WS-TEMP-MATH

ADD P-VAL(IDX-I, 1) P-VAL(IDX-I, 2) P-VAL(IDX-I, 3)

TO WS-TEMP-MATH

COMPUTE P-VAL(IDX-I, 1) = P-VAL(IDX-I, 1) / WS-TEMP-MATH

COMPUTE P-VAL(IDX-I, 2) = P-VAL(IDX-I, 2) / WS-TEMP-MATH

COMPUTE P-VAL(IDX-I, 3) = P-VAL(IDX-I, 3) / WS-TEMP-MATH

loss calculation

Python: loss = -np.mean(np.log(probs[range(n), y]))

COBOL: loop over samples, accumulate negative log probabilities.

* CROSS-ENTROPY LOSS: L = -SUM(Y_TRUE * LOG(P_PRED)).

MOVE 0 TO WS-LOSS

PERFORM VARYING IDX-S FROM 1 BY 1

UNTIL IDX-S > WS-TRAIN-ROWS

COMPUTE IDX-I = WS-IDX(IDX-S)

COMPUTE IDX-J = D-Y(IDX-I) + 1

COMPUTE WS-LOSS = WS-LOSS -

FUNCTION LOG(P-VAL(IDX-I, IDX-J))

END-PERFORM

COMPUTE WS-LOSS = WS-LOSS / WS-TRAIN-ROWS

backpropagation: output gradient

Python: dz2 = probs - y_onehot

COBOL: copy probabilities, then subtract 1 from the true class.

* DERIVATIVE OF SOFTMAX CW CROSS-ENTROPY: DZ2 = P - Y_TRUE.

PERFORM VARYING IDX-J FROM 1 BY 1 UNTIL IDX-J > 3

MOVE P-VAL(IDX-I, IDX-J) TO BP-DZ2(IDX-J)

END-PERFORM

COMPUTE IDX-K = D-Y(IDX-I) + 1

SUBTRACT 1 FROM BP-DZ2(IDX-K)

backpropagation: W2 and b2 gradients

Python: dW2 = h.T @ dz2 / n and db2 = dz2.mean(axis=0)

COBOL: accumulate gradients across all samples, then average during update.

* ACCUMULATE DW2 = H^T * DZ2 | DB2 = DZ2.

PERFORM VARYING IDX-J FROM 1 BY 1 UNTIL IDX-J > 3

COMPUTE DB2-VAL(IDX-J) = DB2-VAL(IDX-J) +

BP-DZ2(IDX-J)

PERFORM VARYING IDX-K FROM 1 BY 1 UNTIL IDX-K > 16

COMPUTE DW2-VAL(IDX-K, IDX-J) =

DW2-VAL(IDX-K, IDX-J) +

(H-VAL(IDX-I, IDX-K) * BP-DZ2(IDX-J))

END-PERFORM

END-PERFORM

backpropagation: hidden layer gradient

Python: dh = dz2 @ W2.T

COBOL: explicit matrix-vector product.

* BACKPROP TO HIDDEN LAYER: DH = DZ2 * W2^T.

PERFORM VARYING IDX-J FROM 1 BY 1 UNTIL IDX-J > 16

MOVE 0 TO BP-DH(IDX-J)

PERFORM VARYING IDX-K FROM 1 BY 1 UNTIL IDX-K > 3

COMPUTE BP-DH(IDX-J) = BP-DH(IDX-J) +

(BP-DZ2(IDX-K) * W2-VAL(IDX-J, IDX-K))

END-PERFORM

backpropagation: ReLU gradient

Python: dz1 = dh * (z1 > 0)

COBOL: IF statement as a gate.

* DERIVATIVE OF RELU: DZ1 = DH IF Z1 > 0 ELSE 0.

IF Z1-VAL(IDX-I, IDX-J) > 0

MOVE BP-DH(IDX-J) TO BP-DZ1(IDX-J)

ELSE

MOVE 0 TO BP-DZ1(IDX-J)

END-IF

backpropagation: W1 and b1 gradients

Python: dW1 = X.T @ dz1 / n

COBOL: accumulate outer products.

* ACCUMULATE DW1 = X^T * DZ1 | DB1 = DZ1.

COMPUTE DB1-VAL(IDX-J) = DB1-VAL(IDX-J) +

BP-DZ1(IDX-J)

IF BP-DZ1(IDX-J) NOT = 0

COMPUTE DW1-VAL(1, IDX-J) =

DW1-VAL(1, IDX-J) +

(D-X1(IDX-I) * BP-DZ1(IDX-J))

COMPUTE DW1-VAL(2, IDX-J) =

DW1-VAL(2, IDX-J) +

(D-X2(IDX-I) * BP-DZ1(IDX-J))

COMPUTE DW1-VAL(3, IDX-J) =

DW1-VAL(3, IDX-J) +

(D-X3(IDX-I) * BP-DZ1(IDX-J))

COMPUTE DW1-VAL(4, IDX-J) =

DW1-VAL(4, IDX-J) +

(D-X4(IDX-I) * BP-DZ1(IDX-J))

END-IF

parameter update

Python: W -= lr * dW

COBOL: compute scaled learning rate once, then apply to all parameters.

* PERFORM PARAMETER UPDATES: PARAM = PARAM - LR * GRADIENT.

COMPUTE WS-TEMP-MATH = WS-LR / WS-TRAIN-ROWS

PERFORM VARYING IDX-I FROM 1 BY 1 UNTIL IDX-I > 16

PERFORM VARYING IDX-J FROM 1 BY 1 UNTIL IDX-J > 3

COMPUTE W2-VAL(IDX-I, IDX-J) =

W2-VAL(IDX-I, IDX-J) -

(WS-TEMP-MATH * DW2-VAL(IDX-I, IDX-J))

END-PERFORM

COMPUTE B1-VAL(IDX-I) = B1-VAL(IDX-I) -

(WS-TEMP-MATH * DB1-VAL(IDX-I))

END-PERFORM

evaluation

Inference is the same forward pass without gradients. Prediction is argmax:

* PREDICATE SELECTION: ARGMAX PROBABILITY.

EVALUATE TRUE

WHEN P-VAL(IDX-I, 1) >= P-VAL(IDX-I, 2) AND

P-VAL(IDX-I, 1) >= P-VAL(IDX-I, 3)

MOVE 0 TO WS-PRED-CLASS

WHEN P-VAL(IDX-I, 2) >= P-VAL(IDX-I, 1) AND

P-VAL(IDX-I, 2) >= P-VAL(IDX-I, 3)

MOVE 1 TO WS-PRED-CLASS

WHEN OTHER

MOVE 2 TO WS-PRED-CLASS

END-EVALUATE

grand finale

To compile these 578 lines of pure madness, just keep calm and use gnucobol:

$ cobc -x -o pengu_nn pengu_nn.cob && ./pengu_nn

LOADED 0333 VALID ROWS.

DATA HOUSEKEEPING COMPLETED.

EPOCH 0000 LOSS: +000000001.098705953

EPOCH 0050 LOSS: +000000000.948385870

EPOCH 0100 LOSS: +000000000.404952448

EPOCH 0150 LOSS: +000000000.254336047

EPOCH 0200 LOSS: +000000000.157729394

EPOCH 0250 LOSS: +000000000.097222933

EPOCH 0300 LOSS: +000000000.067910843

EPOCH 0350 LOSS: +000000000.052804836

EPOCH 0400 LOSS: +000000000.043876194

EPOCH 0450 LOSS: +000000000.037968264

EPOCH 0500 LOSS: +000000000.033755593

TEST ACCURACY: +000000001.000000000

TRAIN ACCURACY: +000000000.988721804

Does it work? Yes. Painfully. Slowly. Correctly.

I know what you are thinking: why on earth I put 500 epochs for such a small dataset? Coz’ we can. 😎

The penguins get classified. The loss goes down. The mainframe hums in approval. Somewhere, a finance department nods without understanding why.

You can find the full working code, including all the ugly declarations I spared you from, in this github repo.

-

yep, I know we don’t need IMS here. I just wanted to flex with that since I don’t get many chances, lol. ↩

Hey, I'd love to hear your thoughts! Just drop me an email.